Simon Hochberger

Life and Work of Simon Hochberger (1906-1947)

In the Maelstrom of the Time.

Life and Work of Simon Hochberger (1906-1947). [1]

By Friedrich Voit

It was the short essay by Leonard Bell The Lost Writer, [2] which prompted my interest in the writer Simon Hochberger and his epic poem Warsaw Ghetto – Tale of Valor, which was published in 1946 in Melbourne in a small booklet. It wasn’t difficult to obtain the text of the poem, for an online facsimile copy of the rather rare original print could be found at the State Library of Victoria (Melbourne). [3] However, only sketchy information about the life and work of the author was available until recently, yet the text of the poem has a poetic power and distinction, which suggests that it can’t have been his first and only literary work. This essay attempts to outline the literary life and career of Simon Hochberger. This is, as will be shown, a biography and career shaped by the forces and catastrophes in Europe of the first half of the 20th century, containing many aspects representative for Jewish lives of this period and from this region.

When Hochberger wrote his epic poem in 1944/5, he was still under the impression of the Warsaw tragedy in 1942/3, but he also felt the redemptive satisfaction of the imminent victory over Nazi Germany and the emerging hope for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. All this underpins the celebratory emotion of the poem.

Hochberger was able to follow the global political events in newspapers available to him in Australia. From its beginnings, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was covered in the English-language press and also documented with photographs. He certainly knew some of the detailed testimonies by eyewitnesses about the life and events in Warsaw under German occupation which had already been published in the English language. [4] Such accounts may also have inspired the form as well as tone of the poem, as its content and structure indicate.

Warsaw Ghetto. Tale of Valor is, as the subtitle suggests, a narrative poem that tells the story of the ghetto uprising in irregular iambic stanzas with a predominantly pentametric rhythm. Hochberger forms a series of vivid images and short scenes into the four parts of the poem.

The Prelude sets out by describing a view of the destroyed ghetto that has been razed to the ground. An image like the one inserted here, [5] may have inspired it.

Warsaw Ghetto destroyed by Germans (1945)

An Observer looks at the destroyed city and notices nearby a few items, a ‘broken twig a stone ̶ a shattered wall’ and a ‘little piece of candle sticking out / Of dusty rubble’, which start to speak ‘Conveying silently their message to the world’.

The stone evokes the once bustling life in the Jewish quarter of the city that has disappeared, and the shattered wall recalls the small, run-down houses where the mostly poor families lived and gathered in the evening. The candle stump brings to mind the many occasions in Jewish life when candles were lit, especially at the end of the week to celebrate the Sabbath. All this ended abruptly when the Germans invaded Poland and established the forced ghetto in Warsaw: ‘The lights went out ...’, a nightmare of persecution and oppression began.

What was about to happen is, as the first Interlude laments first only noticed and mourned by the ‘lonely stars’ and the ’lonely’ moon, while in the last stanza, the ‘wrathful sun’ scorns the 'brutes in black' and warned the Jews of Warsaw to arm themselves inwardly and against external violence: ‘Pray ̶ and be prepared’.

Terror, so the title of the next part, opens with an appeal to God and the question why he does not hear the cries for help of his people at the mercy of the diabolical ‘fiend of man’, and continues with an appeal to the ‘people of the world’ not to close their eyes to the despair, starvation and murder in the ghetto. Two scenes illustrate the crippling horror and inhuman brutality of the Gestapo-men in their black uniforms: a squad of marauding soldiers breaks into a house, stealing what little of value and edibles they can find; one of the intruders grabs Rebb Hersh's beard in humiliating crudeness, dragging him out of the house in front of and away from his wife to forced labour and his death. Of no less unprecedented cruelty is the second scene, in which two drunken soldiers invade a family's home in the evening. They are after the young daughter Malka. While one of them guards the door with a drawn pistol, the other tears off the young woman's clothes in front of those present. Then the brother, a cripple, grabs a bronze candlestick and strikes the rapist down - and is himself shot on the spot. No plea to heaven or confession of sins helped against the nightmare of such murderous acts: ‘The lights were out ...’ a rescue from the omnipresent ‘beast’ seems nowhere in sight.

The three stanzas of the second Interlude introduce the change from powerless defeat against the ever-present violence to the resistance of the desperate, who could no longer accept terror, hunger and annihilation through murder and forced labour without defence:

Foundations of the ghetto started shaking,

The Jews in Warsaw’s ghetto-walls – hit back!

Like a dybbuk, the murdered, robbed of years of their lives, weigh on those still living and demand an act of redemption – setting free the courage of the desperate. With the discovery of an unknown murdered and violated boy, the suppressed despair of those still living turns into ‘burning hate’ that cries out for retribution. A coordinated resistance begins to emerge – The Battle sets in.

With few poignant scenes, Hochberger powerfully describes the desperate fighting, which lasted for one month from April into May 1943. On the eve of Passover, when a squad of ten uniformed henchmen wants to take three old Jews on their way home for forced labour, they ignore the order. But before the German soldiers could punish or shoot the recalcitrants, they were unexpectedly attacked and killed by underground fighters. The ‘holy Jewish war was on [...] for self-respect and faith in man’. The next day the demand of the oppressing force to provide 90 hostages remained unheeded. The ensuing brutal suppression of the uprising that lasted for thirty days is portrayed in brief scenes: a struggle against a vast military superiority, when 40,000 Jews put up a courageous, but from the outset forlorn resistance with only small arms, incendiary bottles and primitive weapons. The final scene pictures the defence of the last house by five young fighters, four men and one woman. The men are quickly overwhelmed and killed, while the soldiers want to take the young woman alive. For a moment, she is able to stop the pursuers with a gush of acid from a jar, and, escaping to the roof, from where, wrapped in the Jewish blue and white flag, she throws herself to her death:

The Warsaw Ghetto was not crushed. It died.

Warshaw Ghetto - Resistance (April 1943)

The poem concludes with a short Epilogue which once more evokes the haunting sight of the destroyed ghetto and the relics – ‘the twig, the stone, the shattered wall, / The little piece of candle’ - that have now told their story. A young Jew visiting the ruins might also come across a stub of a candle, light it and say a Kaddish for those who perished here. ‘The soul of man’, the chronicler is certain, will remember the ‘gallant’ Jews of Warsaw as martyrs who died ‘that Israel may live!’

The impact of the poem is based not least on its form and the dramatic, ballad-like narration. One is reminded of a ballad-singer who, through emphatic delivery, explains and comments on a historical event with striking pictorial scenes and captivates the listener. Hochberger's language is expressive and never slips into sentimentality. He thus succeeds in creating motifs, images and scenes that are memorable and inspire the reader’s imagination. This reveals the extraordinary poetic talent that was denied full development by a premature death.

When the poem was published in Melbourne in 1946, it found wider resonance for some time, especially in the Jewish communities of Australia and New Zealand. Warsaw Ghetto is one of the outstanding early monuments that artists and poets created to the Jewish resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto and against the annihilation of Jewish life in Europe. One may think of Ben Hecht's theatrical show We will never die, with music by Kurt Weill, which was shown in many American cities in 1943/4, Arnold Schönberg's cantata Survivor from Warsaw 1948 or Itzak Katzenelson's great epic Dos lid funm ojsgehargetn yidischen folk, which appeared in Yiddish in 1945 and was translated into several languages in the following years. The fact that Hochberger's poetry has not yet found its place in cultural memory is most likely due to the short life of its author, which was so deeply shaped and impacted by the maelstrom of the time.

Who was Simon Hochberger, the poet of the poem Warsaw Ghetto - Tale of Valor, who is today - unjustly - as forgotten as his poem? It did not prove easy to research the key facts of his biography, even though the Internet, with its wealth of data and websites, provides invaluable help today. What has been found here and there, especially some files of the Australian National Archives (NAA), some of which are now accessible online, make it possible to give at least an outline of Hochberger's life story.

Simon Hochberger came from an Orthodox Jewish family in Austro-Hungarian Galicia. His father Michael Gottlob Hochberger was born in 1876 in Bobowa, which today belongs to Poland, and his mother Frieda (née Storch), two years older than his father, also came from the region. They probably spoke Yiddish with each other, but they also knew the other languages of the area. In an official profile, Michael Hochberger is certified as speaking ‘Hungarian, broken German and a little Polish’. [6] The father is described as a ‘traveller’ and in later documents as a merchant. Simon Hochberger was born on 19 April 1906 in Kesmark (today Kežmarok in Slovakia). Probably for economic reasons, his father moved with his family to Germany shortly afterwards and settled in Essen around 1906/7, where there was already a large community of Jews from Eastern European. Their daughter Selma Sala was born there in 1912. With the fall of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, the family became stateless.

Simon first attended probably the Jewish primary school in Essen. It is not known which secondary school he went to. When he enrolled at Leipzig University for the winter semester of 1924, he gave his father's address as ‘Essen, Kirchstraße 20/I’. [7] Hochberger studied journalism with Karl Bücher, the founder of journalism as an academic discipline, for only one semester at the university [8] and then transferred to the commercial college there, where - as he later stated - he trained as an advertising specialist. [9] After his studies and training, Hochberger first began a career as a journalist in the pre-Hitler years and is said to have written as a correspondent for various liberal newspapers such as the Kölnische Zeitung, the Frankfurter Zeitung and the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung. [10] He later used 'journalist', also 'author' and 'designer' as his job title on various occasions.

As Jews, the perspective on life changed fundamentally for the Hochbergers too when the Nationalsocialists came to power. His parents and sister left Essen and moved to Leipzig, from where they, being stateless, were forcibly expatriated to Poland in 1938. There they returned to Gorlice (formerly Galicia), where they probably still had relatives. Simon Hochberger, for whom there was no longer any professional future in Germany, had already been living in Vienna since 1933, where he worked independently as a ‘designer and signwriter’ until 1938 and as a journalist correspondent for the Neue Wiener Tageblatt. [11] In Vienna, Hochberger married Charlotte Mandowsky (b. 1909) from Hamburg in April 1934, who had studied medicine and practised as a doctor at a Viennese hospital. [12]

When, with the ‘Anschluss’ (the German annexation) of Austria in March 1938, the persecution and destruction of Jewish life set in with vehemence, Hochberger applied for a visa for himself and his wife to the U.S.A. in July 1938. But events caught up with him, so that in March 1939 he took the chance to flee to England with the help of the Council for German Jewry. For over a year he lived in the Kitchener Camp near Sandwich in Kent. [13] The camp had only been set up after the 1938 November pogrom for younger Jewish men persecuted in Austria and Germany, who were waiting as transmigrants for visas to emigrate to other countries such as the U.S.A. or South America. His wife could not accompany him and stayed behind in Vienna. Both must have hoped that Lotte, as she was called, would soon be able to follow him, because Hochberger came to England with a 'big trunk' containing household items - including bed linen, tablecloths and silverware from family possessions, in addition to some books he had acquired in Vienna, Prague, Paris and Zurich. He was also able to take his typewriter and a valuable Rollei camera with him. [14] However, he was not to see his wife again; she seems to have soon lost her job at the hospital and was dependent on financial support from her mother, who lived in Hamburg.

The Kitchener Camp, a former military camp, was largely funded by the German Jewish Aid Committee (London), opened early in 1939, and was run by the brothers Jonas and Phineas May of the Anglo-Jewish Association. All camp residents were obliged to work, mainly preparing the camp for the rapidly growing number of refugees (more than 4000). They were also involved - depending on their professional aptitude - in the administration and food preparation of the camp. Phineas May, who tirelessly looked after the needs of the camp and its inhabitants, organised a varied training and employment programme as 'Sports and Recreation Officer', centred around the professions and talents represented among the refugees. All had to learn English, and special language programmes were offered. An excellent orchestra of refugee musicians, various clubs and sports activities were formed. There was a cinema and concerts, shows and theatre performances were regularly held to make the monotony of camp life more bearable and to which the locals from the surrounding area were invited. Both Phineas May's camp diaries and the Kitchener Camp Review, which he edited and published monthly between March and November 1939, give a vivid picture of the astonishing and varied sporting, cultural and religious activities in the camp. [15]

Hochberger was initially engaged in agricultural work. But he was also involved in cultural activities, which suited his literary and artistic talents and interests. In the June issue of the Camp Review, he published his first contribution, still written in a rather unidiomatic English, a humorous piece What tickles me in Camp, illustrated probably by himself, in which he reflects on some amusing observations and incidents in the unfamiliar camp life. For the following issues he provides several smaller essays, soon with an improved and more fluent English: in the August number, in Zig - Zag, he pokes fun at how a newly trained barber uses his only modest skills to save himself from an embarrassingly difficult situation, and in October, shortly after the outbreak of war, he gives his Impressions of a 'Sand-Bag Filling Party’, which he had joined and which was enthusiastically received by children begging for foreign stamps every morning on the beach and seen off in the evening. These texts, little more than half a page to a page long, were exercises in perfecting himself in the new language. His most significant contribution to the camp newspaper was the three-scene sketch Illustrated Phrase Book printed in September, which mocks a newcomer trying to find his way around the camp with the help of a phrase book. This sketch had been written, as a critic wrote, by ‘our brilliant Mr. S. H........r for a revue show that camp inmates put on in August for the so helpful English friends of the Kitchener Camp’. Hochberger was the driving force behind this show; he is named as the producer and participated himself as MC, introducing the individual acts. The show was repeated several times with great success in front of hundreds of spectators from the camp and local visitors from outside. [16]

The beginning of the war with the invasion of Poland by the German army caused considerable changes for the Kitchener Camp. Rescue operations from Germany and Austria could no longer be organised and the postal services to and from Germany came to a standstill. When from October 1939 foreigners living in England were registered, Hochberger, who had previously declared himself a Polish citizen, was declared stateless and classified as a refugee in Alien Class C, which was subjected to the least restrictions. [17] The desire to be recognised as a Pole may have come from the feeling of belonging to the family expelled to Poland, as well as from solidarity with the nation under attack by Hitler's army.

Like most in the camp, Hochberger immediately enlisted in the National Service and worked with a group filling sandbags to protect the local hospital against feared air raids; he was then assigned to the BBC radio station in Richborough from December 1939 to May 1940. [18]

In January 1940, Hochberger received a letter from an acquaintance in the USA who inquired about the emigration plans of Simon and Lotte Hochberger. Hochberger applied for a Certificate of Identity, hoping to receive a final decision soon. But the plans to emigrate to the USA fell through. With the fall of France, the attitude of the British government towards the 'aliens' changed. It was now considered too risky to house a large group of German-speaking refugees so close to the Channel coast. It was decided to close Kitchener Camp. The remaining inmates were now interned as 'enemy aliens', contrary to their earlier classification, and in May were taken to a camp near Ramsey on the Ilse of Man. They could only take a small suitcase with some clothing and personal belongings, while the rest of their belongings were stored in the Kitchener Camp - and later lost there. [19]

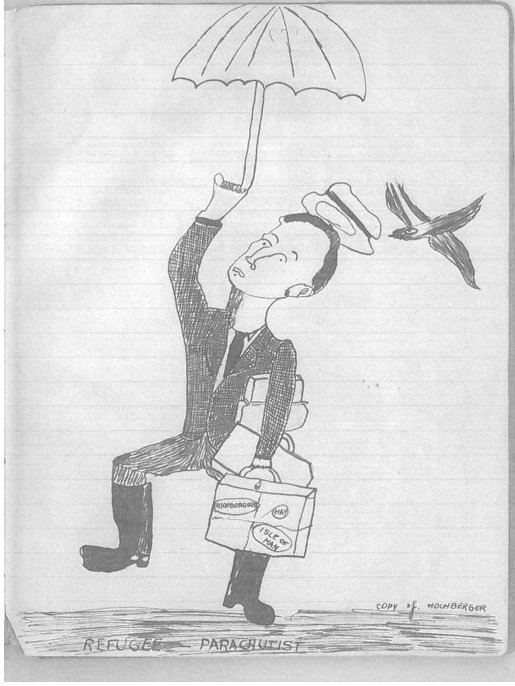

A few weeks later, many of the Kitchener Camp refugees were taken to Liverpool and forcibly deported to Australia together with over 2,000 other internees on the troopship Dunera. Only they learned after a few days at sea that the journey was not to Canada as had been assumed, but to the Pacific continent. The inhumane treatment the internees received from the English escort crew during the almost two-month journey has been extensively described and documented. [20] Already at embarkation, all luggage and personal belongings were taken from the passengers and ransacked and looted before their eyes. The accommodation on the ship was primitive, the sanitary facilities completely inadequate and the soldiers' treatment of the forced passengers harassing and violent. The scandal of this deportation was exposed in the press soon after arrival in Australia and was investigated in court sometime later. Some compensation was granted for the luggage losses suffered, but for many - including Hochberger - the traumatic Dunera experience brought the loss of their last personal belongings. In his claim for damages, [21] Hochberger later listed two losses that must have been particularly close to his heart, in addition to the clothes stolen from his suitcase: the tefillin he had received in Essen in 1919 for his bar mitzvah, and a portfolio, the contents of which he did not specify, but which, along with personal documents, must have contained evidence of his journalistic and literary work. Only his typewriter was found again - albeit damaged. When he left the ship in Sydney in September, Hochberger had nothing more than what he had on his body and with him. This caricature amongst Moshe Chaim Gruenbaums papers, [22] possibly aimed at Hochberger himself, illustrates the turbulent events and the powerlessness of the refugees brought from England during this notorious deportation operation.

Performance Poster ( November 1940; Jewish Museum of Australia, Dunera Collection)

When all the deportees were officially registered on arrival at the first Australian port in Freemantle on the west coast, Hochberger again described himself as a Polish citizen. After a stopover in Melbourne, the Dunera landed in Sydney, where the remaining deportees disembarked, were immediately loaded onto trains and transported inland to Hay, a small town in New South Wales, about 700 km inland from Sydney, where the Australian government, at the instigation of the British, had hastily set up internment camps for prisoners of war and those deported on the Dunera. [23] Hochberger was placed in Camp 7 with other Jewish internees. He was to remain there for nine months. At a registration in October 1940, he stated that he was married to Charlotte Hochberger and named his father Michael Hochberger as his next of kin, who lived in Gorlice (Poland). [24] At that time, however, any postal contact had already become impossible and ceased with both of them.

As in the Kitchener Camp, the internees at Hay also organised a diverse programme of social, educational and cultural activities in order to better bear the remote and barren camp life. Probably because of his experiences at Kitchener Camp, Hochberger was given the role of manager of the Recreation Department. After only a few weeks he produced the first shows on the newly constructed stage of the Camp Theatre.

The first two performances were described as 'variety shows', with the first show performed in November 1940. The premier performance was Hay Fever, a revue featuring a number of short items involving at least 15 performers and musicians. It was closely followed by the second show (also staged in November). It consisted of a number of acts which included the clowns Ric and Rac, a one-man circus, and items such as 'The Naughty Nineties' and 'Fernand and Yvonne'. [25]

Simon Hochberger, ca. January 1942

Hochberger remained in the Hay camp until May 1941, before he was transferred to the Tatura camp in Victoria, about 160 km north of Melbourne, in July, after an interim stay in the Orange camp (about 100 km west of Sydney). These transfers probably had to do with the arrival of Julian Layton, who had come to Australia in the spring of 1941 as a major in the British Army. Layton played a key role in rescuing Jews from Austria and Germany throughout the period of persecutions in the 1930s and during World War II. During extended stays in Vienna, he helped countless Jews escape to England, he was involved in organising the Kindertransporte (children’s transports) in 1938 and took over the running of Kitchener Camp after Phineas May in October 1939. [26] In the aftermath of the Dunera scandal, the British government sent him to Australia to help Jewish refugees who had previously been interned in England - unjustly, as was now admitted - with their claims for reparations and their release from the internment camps. To this end, in September 1941, the U.K. Male Internees interned in Australia had to fill out another questionnaire. Hochberger’s contains telling information about his life situation at the time. He describes himself as ‘Author, Designer’, names his wife ‘Charlotte Mandowsky’ and gives her address in Vienna (‘39, Berggasse’). He answers the final question about his reasons for preferring to be interned in Great Britain, or released from any internment, rather than stay in Australia:

Owing to my Polish nationality I do not see any reason for my being kept interned anywhere.

[…] I am acknowledged as a Polish national by the British authorities according to my certificate of registration. I was expressly exempt from internment according to [the] list of May 1940, issued by the Sandwich Police Station, and was interned only by mistake. [27]

On 1 January 1942, Hochberger informed Major J. D. Layton that he had applied for release from internment and hoped to return to England ‘as a free man’. His application was accompanied by an identification photo, one of the few surviving photos showing Hochberger. [28] He received the promise to be able to return a short time later, [29] but he did not take up this opportunity, probably because of the news he had received in those weeks about the death of his parents in Poland and the suicide of his wife in Vienna. A return to Europe now seemed meaningless, even abhorrent. Instead, Hochberger volunteered for service in a Labour Corps of the Australian army. At the beginning of 1942, he was employed harvesting fruit in the Shepparton Destrict, not far from Tatura, before enrolling with the 8th Australian Employment Company in April. There were several such labour battalions in the Australian Army in which non-Australians served. They were not involved with combat service, but mostly with loading and unloading transport trains and other war-related work. The 8th Employment Company was stationed at Caulfield (Melbourne). For many, this brought them back into contact with a major city after a long time, which they could visit in their spare time. Some were even allowed to take up training or study, preparing their way into a new civilian career. [30]

When Hochberger filled out the Mobilisation Attestation Form on joining the army in April 1942, [31] he described himself as a widower for the first time. Between his release from internment in January and his joining the Australian army, he had received a letter from a maternal uncle, Moritz (Morris) Storch, [32] from Los Angeles, telling him the worst possible news about his parents and wife, whose fates he had apparently not heard about for some time:

Dear Simon,You will certainly be surprised to receive a letter from me as we are here since a short time, after having suffered very much in Poland during the war.

Just now I received a letter from Dora Altschiller, from Santiago de Chile, requesting me to write to you as the mail to Australia goes better from me.

It is for me a weary duty to inform you that both your parents, father and mother, died in January 1941, in Gorlice, Poland. They probably were so weak by the shortage of food in Poland that, when your father first became sick, he could not resist the illness and died. 14 days later your mother, sitting at the table, fell asleep and didn’t awake any more, probably by heart troubles, caused by the excitement over your father’s death. Your father died January 8, 1941, and your mother January 23, 1941. [33]

I am very much depressed that your mother was the first[!] of us who died in the war among us. Your sister Sella[!] is now by herself in Grybow, Poland, at our relatives. And the only thing which she is keeping writing to Dora Altschiller, is to inform you about the death of your parents and to request you to say Kaddish for them. [34]

But that is not the only bad news I have to tell you. I have to inform you that your wife Lotte committed suicide in Vienna, February 15, 1941, because not being able to leave Germany and as the Germans threatened the Jews in Vienna to send them to a concentration camp to Lublin in Poland, where now there are a lot of Jews living under horrible conditions.

We hope that this letter will reach you and you will be able to pray for your parents and wife as Sella requests you. Please, write us confirming that this letter reached you. We hope that we shall see you again after the war when Hitler will be defeated, and everybody will have the freedom again which Hitler took away from everybody in Europe.

With lots of love from us all, your uncle

Moritz

In 1946, he would dedicate his poem Warsaw Ghetto - Tale of Valor to his sister Selma, the only survivor of his immediate family in 1941.

Little is known about Hochberger's life in the Tatura camp and during his three years with the army at Caulfield. In addition to the work he was called upon to do, however, he will have continued to pursue his artistic and literary interests there as far as he had time. This is attested to by the lyrics for two song texts from 1943, which were written in collaboration with the musician and composer Werner Baer (1914-1992). Baer came from Berlin and was able to flee from Germany to Singapore with his wife in November 1938 after his release from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. From there he travelled on to Australia in 1940, where he was interned as a refugee in Tatura Camp 3. It was here that he met Hochberger. Like Hochberger, Baer joined the 8th Employment Company after his release from the camp. Baer was naturalised after the war and then worked for many years in Australia's musical life, especially in Sydney, as a musician and singing teacher. [35]

At a music competition of the Australian Brodcasting Commission in August 1943, Werner Baer and Simon Hochberger won the main prize for their song Sounds of Europe out of 147 compositions submitted. The lyrics and the musical setting of this song reveal two experienced and accomplished artists who effectively appeal to their listeners in their agitational and rhythmically structured composition. The stanzas recall the brutal oppression of Europe by Hitler's army and, in the final stanza, praise the resistance of the ‘people of Europe’ in anticipation of the Allied victory:

Sounds of Europe.Listen, brother – listen, sister:

From far comes the sound of their trampling feet,

Listen, lady – listen, mister.

They trample through courtyard and street.

They trample the skin of your body and bone.

They trample your last bit of breath,

They’re crushing your world into graveyards of stone,

They trample your freedom to death.

Listen, brother – listen, sister:

They’re trampling, the earth is becoming sore,

Listen, worker – listen, soldier:

Their heels beat the rhythm of war.

Listen, brother – listen, sister:

From far comes the sound of a clanking chain,

Listen, lady – listen, mister:

Defenceless are tortured and slain.

The gallows of Europe reach out for the sky,

The hangmen of Europe don’t fail,

They’re tapping the globe and they smile and stand by - -

There are human bodies for sale.

Listen, brother- listen, sister:

The victims prepare a tremendous bill,

Listen, worker – listen soldier:

The sound of the chain’s getting shrill.

Listen, brother – listen, sister:

From far comes the sound of a thundering flame,

Listen, lady – listen, mister:

To blast all you love is their game.

They storm through the land and they rave and they rob

Decaying is all in their grip,

With poison and gun they are doing the job,

Their tokens are death-head and whip,

Listen, brother – listen sister:

The fiend of all mankind has broken loose,

Listen, worker – listen soldier:

His victims stand up and accuse.

Listen, brother – listen, sister:

From far comes the rhythmic sound of a drum,

Listen, lady – listen, mister:

The sound enters palace and slum.

The conquered are stirring, they pull at their chain,

A glint of new hope in their eyes,

They listen and find all their courage again,

The people of Europe – they rise …..

Listen, brother – listen sister:

The armies of freedom are on their way,

Forward, worker – forward, soldier!

The hangman of Europe will pay!

The second song Underground was probably written at the same time. In it, Hochberger hails the resistance fighters organised in the underground – ‘so silent and brave [...] determined and stern’ - in the occupied countries of Europe. Here is the last of the song's three verses:

I know of an army, so small and so great,

Its soldiers won't ever forgive,

They guard all their love and they store all their hate,

They're helping to master their continents fate,

Someday once again it will live ....

A handful of heroes walk out of the night,

Their anthem is simple and sound:

They wait and they watch and they work and they fight

U n d e r g r o u n d.

Both songs [36] forcefully respond to and reflect the world situation at the time. The pathos and theme of the songs, anticipate the mood and topic of the great commemorative poem on the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, which Hochberger probably began to conceive soon after these songs.

Even before his discharge from the military, Hochberger was able to resume his journalistic career. As early as May 1945, he started contributing to the Melbourne-based journal The Zionist. A Monthly Review of Jewish Affairs, a leading Jewish monthly founded by Aaron L. Patkin in 1943. Patkin (1883-1950), of Russian origin, had practised law in Moscow before emigrating to Australia in 1927 after years of exile in Germany. There he established himself as a businessman and became one of the leading Zionist intellectuals. [37] In The Zionist, Jewish but also some non-Jewish authors reported and discussed the extermination of the Jews in Europe, but above all the developments in Palestine and the efforts to establish a Jewish ‘homeland’ there, a state that could grant Jews state protection. To give an indication of the high standard of the journal, only three authors and their contributions are highlighted: such as the lecture ‘Zionism from Outside’ by the Danish religious philosopher Greta Hort, [38] who had been working at the university in Melbourne since 1938, or report by Erika Mann, the daughter of Thomas Mann, on her visit to Palestine [39] and the essay ‘Observations on Cain’ by the German-born philosopher and economist Kurt Singer, who had moved to Australia from Japan in 1939. [40]

Hochberger's first contribution to The Zionist was the essay ‘The Theatre of the Jewish People’ about the Habimah Theatre. In it, he outlines the genesis of the first Hebrew theatre during the revolutionary period in Russia, how it found international recognition in Europe and the USA with the much-praised production of Dybuk (1922) by S. Anski, before the group then established itself in Tel Aviv from 1928 and developed there into the Jewish national theatre in Palestine. Against the background of the Jewish catastrophe in Europe, Hochberger viewed Habimah as a new beginning of Jewish culture in Palestine:

To-day the work of the first few pioneers is deeply rooted in the communal life of Eretz Israel, representing one of the strongest pillars of Palestinian culture from which the spiritual light radiates and lends brightness to every corner of the Middle-East. [41]

His second essay, ‘Notes Around Pnina’, which The Zionist published two months later, [42] demonstrates how much English had become Hochberger's first language, the language of his everyday life and writing. In his essay, he celebrated the young pianist Pnina Salzmann, born in Tel Aviv in 1922, who was then just at the beginning of her international career and had come to Australia for several concerts. Hochberger was not writing as a music critic, as he emphasises, but - as with the Habimah Theatre - he was interested in experiencing new Jewish culture developing in Palestine. The concerts of the ‘Palestinian Jewess’ Pnina Salzmann filled him with pride as a Jew and he even saw her piano playing - like any form of art - as a possible weapon in overcoming millennia of anti-Semitism. He gave expression to this utopian hope then, as still today, utopian hope in a thought experiment in the closing paragraphs:

The Jews in the audience have a deep feeling of satisfaction, reaching far beyond the enjoyment of the purely artistic in Pnina’s performance. They see themselves impersonated by this brilliant woman and, simultaneously, see her as a being of their own kith and kin.

It is a glorious gift Pnina has brought to the Jews of this community. She not only makes them proud of her – she makes them proud of themselves. Which is perhaps the best you can give to any human being and, indeed, the very best you can give to a Jew in our times.

They conceive her art as a link between themselves and their gentile co-listeners, and through many a Jewish mind this thought might flash towards them:

Listen to her and hear the message she gives. The message of art, uniting the human souls of the world, the message of beauty, enriching the earthly path of man, and, perhaps most important of all, the message of harmony, which, applied to the relations between the peoples of the earth, rests on the three pillars: Freedom, Justice and Brotherhood.

Possibly now, at this very moment, you would understand our feelings, perceive the tragedy of a people which has been in a state of self-defence for the last two millenniums and decimated during the last decade. Go and take tonight’s message out into the streets, into your homes, to your meetings and challenge those who mean harm to us. (And to you).

As in other Jewish communities in Australia and New Zealand, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising had been commemorated in Melbourne every year since 1944 towards the end of April. This was called for and reported on in The Zionist. The April issues of the journal always carried their own contributions and those reprinted from the international press - essays, poems, and even illustrations commemorating the uprising. On the commemorative pages of the April 1946 issue, Hochberg's poem Warsaw Ghetto was introduced with an excerpt entitled ‘Terror’. [43]

The poem was published a short time later as a simple, slender booklet of 36 pages with an expressionist, dramatic cover illustration by a small publishing house, the Oyfboy Publishing Co. in Melbourne. It seems to have been the first independent publication of this publisher which at that time also published the literary Yiddish monthly of the same name, Oyfboy (Yid. 'building-up'). [44]

Warsaw Ghetto soon attracted attention and the publication of the poem was remarked upon in several Australian newspapers. Reviewers emphasised the poetic power of the poem, even where non-idiomatic language was occasionally objected to. One critic, alluding to the subtitle, rightly emphasised the poem's apparent formal simplicity: ‘The style of the poem is not heroic - its simplicity is in keeping with its subject, emphasizing that it would achieve its forcefulness most effectively in public performances:

A wide audience might be reached for the necessary truth of this work if it were rehearsed and recited at clubs and theatres with perhaps the Interludes as a chorus. [45]

It may have been through this suggestion that parts of the poem were recited ‘by the well-known elocutionist, Betty Perlman, in a most expressive style’ at the commemoration of the Warsaw Uprising at the Kadimah Hall in Melbourne the following year. [46]

Even before the publication of his poem, Hochberger had found a new circle of acquaintances in Melbourne and had become a respected member of the city's literary scene. As a member of the local PEN club, he gave several lectures on theatre and art. With Aaron L. Patkin, the editor of the Zionist, he soon had more in common than their Eastern European origins. In mid-1946, he joined the magazine as a permanent staff member ‘with all the spirit of a European intellectual and the vision of a talented artist’, as Patkin regretfully praised him when he informed readers [47] in June 1947 that Hochberger was leaving the editorial office to go to New Zealand, where he had been offered the editorship of the Jewish Chronicle, the Official Organ of the Zionist Council of New Zealand, the ‘twin brother of The Zionist’, in Wellington.

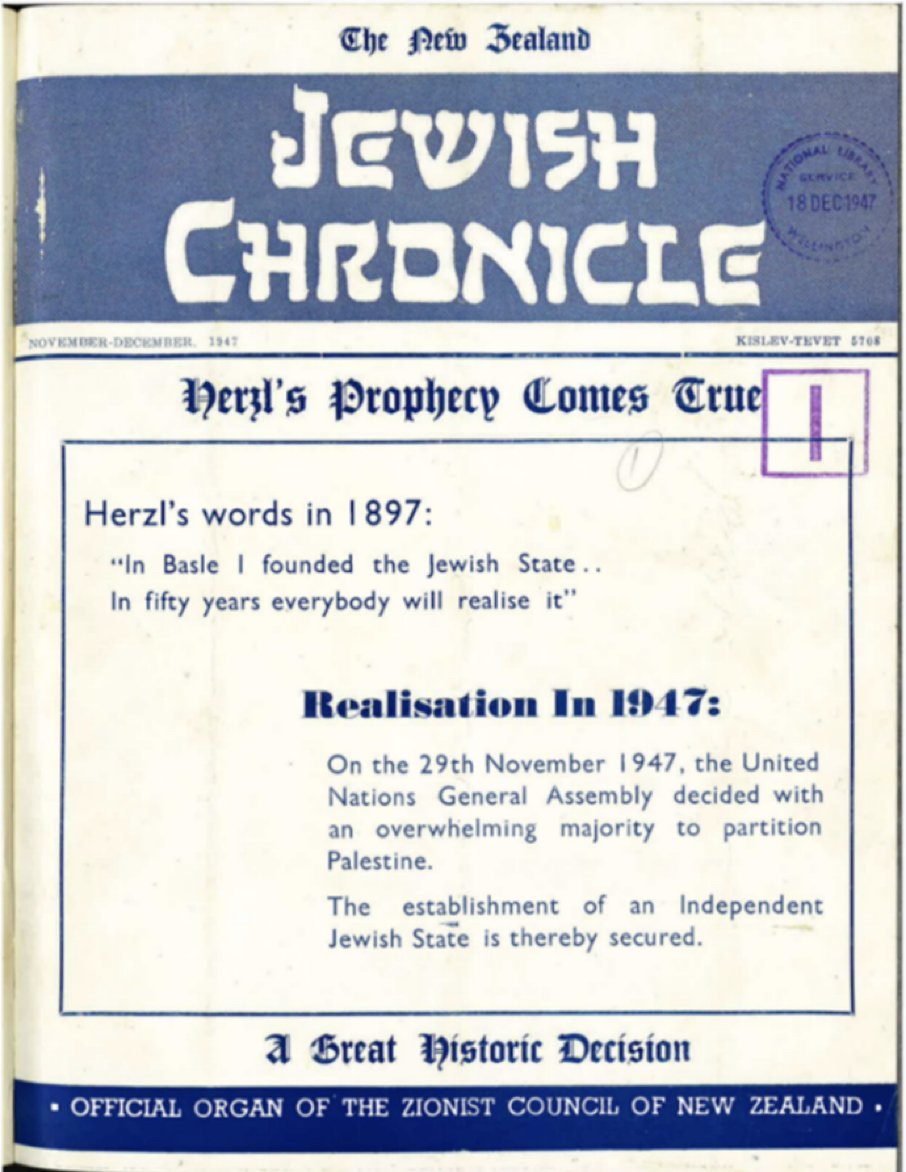

Hochberger did not come to New Zealand completely unknown. In the issue before he took over the editorship he took over with the July/August issue, the Jewish Chronicle in May 1947 had published the passage ‘Terror’ from the poem Warsaw Ghetto, which had already been printed in The Zionist in March 1946.. He was also appointed ‘Secretary of the N. Z. Zionist Council’ and was therefore part of the governing body of a central institution NZ’s Jewish community. Hochberger's work, however, was short-lived. He had supervised only four issues when he died unexpectedly a few months later. Only one more contribution was signed with his name, a slightly edited reprint of his Habimah essay, [48] which The Zionist had already brought out in 1945. Nevertheless, one gets an impression of his journalistic writing and his Zionist thinking from the unsigned editorials, the 'Comments', which open the four issues he edited and - one may assume - were written by him.

The editorials support and inform about the position of the Jewish Agency as the official and elected representative of the Yishuv, the Jews living in Palestine at that time. In ‘Support for Leadership’ (July/August 1947), the editorial argues strongly for a recently passed UN resolution against all Arab and Jewish terrorist activities and explicitly condemns the terror of the Irgun, which endangers any ‘peaceful achievement of our Zionist aims’, especially in view of the forthcoming UN partition decision on Palestine. In the September issue, the comment under the title ‘Hope for Solution’ re-prints a statement by Rabbi Dr. A. H. Silver at the Zurich Conference of the General Zionist Council, expressing hope for a peaceful solution and recommending working towards an ‘economic union between the Jewish and Arab states’. The increasing tension between the Yishuv and the Arab governments before the decisive decision is the subject of the editorial ‘The Economic Threats’ (October 1947). The threat of a ‘general boycott by Arabs’ in the event of the establishment of a Jewish state is put into perspective with the reference to the dependence of the Arab economy on Western capital.

The last issue edited by Hochberger, the November/December issue, already shows on the front page the liberating relief and overwhelming joy over the historic UN decision of 29 November 1947, which recommended the partition of Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. The editorial ‘The Great Opportunity’, unusually long this time, not only welcomes the goal finally achieved:

After the many long years of unparalleled humiliation and persecution which found their infernal climax in Hitler’s crematoria, the Jewish people will, at last, have an independent State which, however small its area, means FREEDOM and SECURITY. This is the outcome of the hour.

At the same time, there is an energetic call for the already existing institutions of the Yishuv, such as administration, police, etc., to be immediately organised and provided by the state. At the same time, however, the goal of a peaceful coexistence of Jews and Arabs should not be lost from sight:

The offer of peace and friendship which has been extended to the Arabs by Dr. Hillel Silver should not remain unheeded. The hour calls for a determined effort on part of the Jewish leaders to join hands with the progressive Arab forces for peaceful and fruitful collaboration.

Hochberger lived to see the UN decision to partition Palestine, but not the proclamation of the State of Israel in May 1948. On 13 December 1947, the 41-year-old succumbed unexpectedly to a coronary thrombosis. [49] The following day he was buried in the Karori Cemetery in Wellington, accompanied by a ‘wide circle of friends’ whom he had found in New Zealand too, but ‘in the absence of any immediate family’; [50] all close relatives had perished in the Shoa.

Newspapers in Australia also reported his death and remembered his epic poem Warsaw Ghetto - Tale of Valor. Aaron L Patkin commemorated him in The Zionist with an in-depth portrait of the journalist and poet to whom he had been close for a number of years and whose so much more promising artistic and literary work had been cut short by a far too early death: [51]

His sudden and premature death at the age of 42[!] in the far-away Wellington in New Zealand moved us all, his numerous friends and co-workers, to a sense of profound grief. Simon Hochberger landed in Australia on the waves of the spiritual black-out which engulfed the British islands in the calamitous year of 1940. He was one of the many thousands of Jewish refugees from the hell of Hitler’s Europe who were given asylum in the pre-war years in England. Overnight, however, a mass expulsion of these refugees took place to the remotest corner of the Empire. Simon Hochberger thus entered the gates of free Australia through the back door of the internment camp. Fortunately, he, as many others of his comrades in disaster, did not judge Australia by the physical and moral standard of Hay in New South Wales and Tatura in Victoria. He bought his freedom at the highest human price—he joined the Australian military forces as a private, fully conscious of his duty as a soldier in the great army of struggle against the bestial forces of Nazism and Fascism. His literary and artistic gifts, his inexhaustible creative energy, his amazing versatility in all branches of art—prose and poetry, theatre and painting, literary criticism and good journalism—opened him the doors of the Australian literary and artistic circles. He was received there with open arms and met with full appreciation of his great talents and profundity of thought. He won the A.B.C. competition for his dramatic poems, “Sounds of Europe” and “Underground”; he was acclaimed for his third remarkable poem, “Warsaw Ghetto,” which revealed with unsurpassed poetic vision a message for “all human beings born like you and me.” He was a member of the Pen Club, where his addresses on theatre and art were not only interesting but also highly provocative. Indeed, the late Simon Hochberger did not land in Australia empty-handed. He carried in his soul memories of a great past, a rich treasure of knowledge and culture. A European by education and upbringing, a graduate of Leipzig University and a staff-correspondent of the pre-Hitler German liberal press, “Koelnische Zeitung,” “Frankfurter Zeitung,” “Berliner Illustrierter Zeitung”—his spiritual background constituted a happy merger of two civilisations—European and Jewish. It is difficult to assess which of these two streams prevailed in the moulding of his personality. Yet one must say that his love of his people, his deep respect for Jewish cultural values, Jewish history, literature, philosophy, etc. was in the nature of a spontaneous passion communicated by generations of Jewish ancestry. His Zionism was prompted much less by the destructive forces of anti-Semitism than by the belief in the great civilising mission of Israel. He witnessed the final act of the great Jewish drama in exile and his sub-conscious yearning for an integral Jewish culture was transformed into a fighting spirit for the fulfilment of the dreams and aspirations of the Jewish masses. He dedicated his pen and brush to the cause of national liberation—and not only his poetical works, but also a number of his character portraits revealed unmistakably how the Zionist ideal was inseparable from his very existence as an artist and a thinker. At one time he joined the editorial staff of “The Zionist,” assisting the Editor in his arduous task. He left an indelible mark on the trend and literary standard of our journal, to which he brought the noblest traditions of the pre-totalitarian European press. His death is a great and irreparable loss to the intellectually poor Jewish communities of the Southern Hemisphere. But, above all, he will be sadly missed by his old and new friends who learned to enjoy his company and admire his creative energy. He belonged to those chosen by God and Nature of whom the poet said: “He whom the gods love dies young.” [52] His physical remains descended to the grave, his soul engraved in works of art and poetry lives on.

Friends in Australia donated a memorial garden of 100 trees to Simon Hochberger a little later, which was planted in Erez Israel. [53]

Footnotes

1 This is a translated and adapted version of the biographical essay in: Simon Hochberger: Warsaw Ghetto. Hrsg., Übertragen und mit einem Nachwort von Friedrich Voit. In: Aschkenas, Bd. 30(1), 2020, pp. 109–149.

2 Leonard Bell / Diana Morrow (Hgg.): Jewish Lives in New Zealand. A History. Auckland 2012, S. 123.

3 State Library of Victoria, Melbourne: DeliveryManagerServlet (slv.vic.gov.au) [last accessed 6.5.2023]

4 Cf. Reca Stone, Revolt in the Ghetto. (Sydney 1944) or the reort by Pierre van Paassen “Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto”, which also had appeared in Australia, in: The Hebrew Standart of Australasia, Vol. 50, No. 47, April 26, 1945, pp 1f. Hochberger might also have known Mary Berg’s Warsaw Ghetto. A Diary, which had been published in 1945 in New York (parts of it had already been published in Jewish journals e.g in the German exil journal Aufbau (September 1944-February 1945).

5 Warsaw Ghetto destroyed by Germans, 1945.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

6 The Information about the parents is based on the Central Database of Shoa Victims (Yad Vashem) and a warrant of apprehension issued for the father in the advertiser Öffentlichen Anzeiger Nr. 185, Düsseldorf, 2 August 1907.

7 Today: Kreuzkirchstraße in the centre of Essen.

8 According to documents in the archive of the university Hochberger, as a stateless citizen, was only allowed to take a two-year undergraduate degree.

9 In a questionnaire Hochberger described his academic training in 1941: ‘Studied Economics at the University and Academy of Economics at Leipzig with special courses of technique of commercial propaganda.” (NAA A367, C62925, p. 8).

10 A. L. Patkin lists these newspapers in his obituary on Hochberger (The Zionist, Dec. 1947 / Jan. 1948, p. 23). The obituary in the NZ Jewish Chronicle (Feb. 1948) mentioned that he was part of the editorial team of the Berliner Tageblatt.

11 This is stated by Hochberger in the questionnaire mentioned in footnote 8 (NAA A367, C62925, p. 20). – The Austrian Online-Newspaper Archive ANNO lists two literary articles by Sid Hochberger, who we can assume is identical with Simon Hochberger: a witty piece ‘Der unheilvolle Bart’ (The calamitous beard) in Das kleine Blatt 14 May 1935, p. 5 and a travel report ‘Die Königin der Nacht von Sarajevo’ (The queen of the night in Sarajevo) in Neues Wiener Journal 7 October 1935, p. 17.

12 On Charlotte Mandowsky and the tragic fate of her and her family detailed information can be found on the web page http://stolpersteine-hamburg.de/index.php (accessed 12.5.2023).

13 For the Kitchener Camp cf. the web page http://www.kitchenercamp.co.uk/, where many documents and information are provided, including some on Hochberger, as well as the book by Clare Ungerson, Four Thousand Lives: The Rescue of German Jews to Britain, 1939. The History Press: Stroud 2014.

14 Cf. the Hochberger file held in the archive of the World Jewish Relief (https://www.worldjewishrelief.org/).

15 The diaries and copies of the Kitchener Camp Review can be found in the Kitchener Camp web page (cf. footnote 12).

16 The show is reviewed in the Kitchener Camp Review September 1939, p. 13, together with the text p.13-15. Phineas May mentions the show on 19 and 20 August, where he also calls Hochberger his ‘chief assistant’.

17 See Hochberger's registration card ‘Male Enemy Alien Exemption from Internment – Refugee’ in the National Archives, Home Office: Aliens Department: Internees Index, 1939-1947 (a facsimile can be found on the Kitchener Camp website).

18 Cf. Moshe Chaim Gruenbaum’s diary entry (accessible on the Kitchener Camp website), who also lived in Kitchener Camp at the time, from 10.12.1940: ‘The army authorities were setting up a radio station on a site opposite the camp. It was to be a service that would listen in to all German broadcasters. [...] The work required me to sit in front of a radio receiver and listen in on the Deutschland transmitter, or Breslau, Hamburg, and also Warsaw.’

19 Cf. Hochberger's claim for damages 1943 (archives of World Jewish Relief, London).

20 There are a number of instructive websites on the deportation transport on the Dunera in the summer of 1940, for example from the National Museum Australia (https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/dunera-boys), from the Jewish Museum of Australia (http://imu.jewishmuseum.com.au/collections/#imu[browse=enarratives.28) or on the website on the Kitchener Camp (http://www.kitchenercamp.co.uk/research/hmt-dunera/), where one can find a transcription of the detailed and impressive description of the affair and its reappraisal in the records of Moshe Chaim Gruenbaum.

21 Cf. Hochberger's 'Claim for Compensation', completed on 17.4.1941 in Hay (NAA A367, C62925, p. 16/7).

22 The caricature is taken from the diary of Moshe Chaim Gruenbaum (http://www.kitchenercamp.co.uk/when-war-began/). The stickers on the suitcase refer to Kitchener Camp, Richborough, the deportation to the Isle of Man and the Australian camp in Hay. The reference "copy of Hochberger" may refer to both the caricaturist and the caricatured.

23 For the camps in Hay, cf. The Wartime Camps in Hay. A collection of first-hand accounts, artwork, newspaper articles, photographs and other documents from the files of the Hay Historical Society. Designed by Ian and Caroline Merrylees. Compiled by Caroline Merrylees. Hay Historical Society: Hay 2006

24 NAA: MP1103/2, E39787.

25 Haywire, p. 91.

26 On Julian Layton cf. http://www.kitchenercamp.co.uk/research/julian-layton/.

27 Cf. Hochberger’s Record of U.K. Male Internees interned in Australia (NAA A367, C62925, S. 8/9).

28 NAA A367, C62925, p. 13

29 Cf. NAA A367, C62925, pp. 18/19.

30 Cf. June Factor, ‘Forgotten Soldiers: Aliens in the Australian Army’s Employment Companies during World War II’, http://www.yosselbirstein.org/pdf/eng/other/Forgotten_Soldiers.pdf).

31 NAA B884, V377697, pp. 2/3.

32 NAA A367, C62925, S. 5. – The undated letter is only known in an English translation from 1945, but Hochberger must have received the original letter already before April 1942, for in the Mobilization Attestation Form he refers to his uncle Morris Storch as his ‘next of kin’.

33 The Central Database of Shoa Victims (Yad Vashem) lists Michael und Frida Hochberger as ‘murdered’ in Gribov (Polen).

34 The Central Database of Shoa Victims (Yad Vashem) mentions Selma Sala Hochberger as ‘murdered in the Shoah’ without specifying the place and year of death.

35 On Werner Baer cf. John Carmody in Australian Dictionary of Biography (online: http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/baer-werner-felix-23082).

36 The two songs (scores and lyrics) are held in the estate of Werner Baer (Australian Music Centre Archive, National Library of Australia 6540946; MUS N AMC Baer 1/ Baer 3).

37 On Patkin, see the biographical essay by his granddaughter Vivien Altman, "'The Spark in the Ash'," in: Australia Jewish Historical Journal, Vol. 23, Part I, 2016, pp. 79-92.

38 The Zionist, Sept. 1943, pp. 13-15.

39 The Zionist, July 1944, pp. 6-7.

40 The Zionist, Aug. 1944, pp. 40-41.

41 The Zionist, May 1945, p. 27. Hochberger's essay is followed by Aaron L. Patkin’s memoir The Dybuk. Some reminiscences of a great theatrical achievement’ (p. 27f.); Patkin may have attended a performance in Moscow.

42 The Zionist, July 1945, pp. 19f

43 The Zionist, April 1946, p. 9. Printed were six stanzas from the second part of the poem ‘Terror’ beginning with the stanza "The time escaped its own established rules" (pp. 21 and 23).

44 The journal by a group of authors writing in Yiddish appeared from September 1945 to January/February 1948, and was running for twenty six issues. The editors were the author[s] Herz Bergner, Ber Rozen, Victoria and Hans Kimmel, and Abraham Shulman. It was printed by A. Maller, Excelsior Printing Co., Melbourne and published by L. Fink, ‘Oyfboy" Publishing Co.’. (https://judaica.library.sydney.edu.au/bibliography/yiddish%20periodicals.html). - The Australian National Library lists a total of only three titles by Oyfboy Publishing, published between 1946 and 1950.

45 Joanne McAulay in: The Zionist, May 1946, p. 26.

46 Cf. ‘Warsaw Ghetto Commemoration’, in: The Zionist, April 1947, p. 29.

47 Cf. The Zionist, June 1947, S. 4.

48 ‘Thirty Years ‚Habimah’ in: Jewish Chronicle, September 1947, pp. 10-12

49 Registrar of Births, Deaths & marriages, New Zealand No. 1947031190.

50 ‘In Memoriam - Simon Hochberger’, in: Jewish Chronicle, February 1948, p. 2. The photograph inserted here is taken from this obituary. - Since Hochberger had no relatives in Wellington, there were enquiries about his will, which was written down in 1943. In 1949, Margaret Brecher from Sydney, Hochberger's executor, applied for a Grant of Probate (cf. ‘Law Notices’, in: The Age (Melbourne), Sat 16 Jul 1949, p. 19). No further information is known to date.

51 ‘Simon Hochberger’, in The Zionist, December/January 1947/8, p. 23.

52 A widespread saying from antiquity, from Menander to Plautus to Byron.

53 Cf. the appeal for donations for this in: The Zionist, April 1948, p. 23. - The donation is also recorded at the Israel National Fund, but unfortunately the files no longer provide information on where the trees were planted in Israel (for this information I thank Markus Wenninger, Klagenfurt).